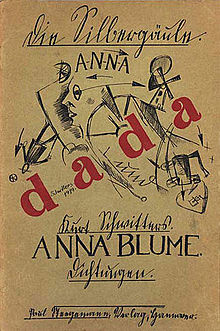

What is Dada? Is it an art movement? A way of thinking? Or is it all just strange words and quirky images? Actually, Dada was an art movement and school founded and begun by a group of avant-garde artists in Zurich in the early 20th century who were dissatisfied about art, the war, and the world in general. And even though Dada brought about changes in art, it wasn’t a traditional art movement.

Dada art was intended to be ugly, weird, and in every possible way the opposite of traditional art. In other words, anti-art. Its founders’ goal was to shake the art world to its core while protesting the war.

Dadaism rejected reason and logic, but prized nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestos, art theory, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. In addition to being anti-war, Dada was also anti-bourgeois and had political affinities with the radical left.

Dadaist Paintings | Image Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Web Gallery, and Wikipedia

Dada activities included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art and Fluxus. Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of anti-art to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism.

The Dadaists imitated the techniques developed such as collage, assenblage, or readymades during the cubist movement through the pasting of cut pieces of paper items, but extended their art to encompass items such as transportation tickets, maps, plastic wrappers, etc. to portray aspects of life, rather than representing objects viewed as still life.

The Dadaists used scissors and glue rather than paintbrushes and paints to express their views of modern life through images presented by the media. A variation on the collage technique, photomontage utilized actual or reproductions of real photographs printed in the press. In Cologne, Max Ernst used images from World War I to illustrate messages of the destruction of war.

Some Dada collage or montage seems more traditional, and other readymades were inspirational, and some Dada artwork was made by trash or recycled materials. Dada art was visually unexpected. The artists’ goal was to stand out from other art forms and be uniquely outstanding, but it is controversial. Some, like Hans Richter, said that Dada was not art, but other said that Dada is a non-art art. However, Dada art continues to influence contemporary artists, graphic designers, and photographers today.

Key figures in the movement included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Richard Huelsenbeck, Max Ernst, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, and Kurt Schwitters.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was a French-American painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Dadaism and conceptual art, although not directly associated with Dada groups. Duchamp is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the twentieth century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture. Duchamp has had an immense impact on twentieth-century and twenty first-century art. By World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists (like Henri Matisse) as “retinal” art, intended only to please the eye. Instead, Duchamp wanted to put art back in the service of the mind.

“Readymades” were found objects which Duchamp chose and presented as art. In 1913, Duchamp installed a Bicycle Wheel in his studio. However, the idea of Readymades did not fully develop until 1915. The idea was to question the very notion of Art, and the adoration of art, which Duchamp found “unnecessary”.

Perhaps the most famous and controversial Dada artwork of all was Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain made in 1917. It consisted only of a urinal set on its back, but it raised a powerful question: “What exactly is worthy to be called art?” After all, this artwork is just an ugly toilet.

Duchamp is considered by many to be one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and his output influenced the development of post–World War I Western art. He advised modern art collectors, such as Peggy Guggenheim and other prominent figures, thereby helping to shape the tastes of Western art during this period. He challenged conventional thought about artistic processes and rejected the emerging art market, through subversive anti-art. He famously dubbed a urinal art and named it Fountain. Duchamp produced relatively few artworks, while remaining mostly aloof of the avant-garde circles of his time. He went on to pretend to abandon art and devote the rest of his life to chess, while secretly continuing to make art.

Duchamp in his later life explicitly expressed negativity towards art itself. In a BBC interview with Duchamp conducted by Joan Bakewell in 1966 Duchamp compared art with religion, whereby he stated that he wished to do away with art the same way many have done away with religion. Duchamp goes on to explain to the interviewer that “the word art etymologically means to do”, that art means activity of any kind, and that it is our society that creates “purely artificial” distinctions of being an artist.

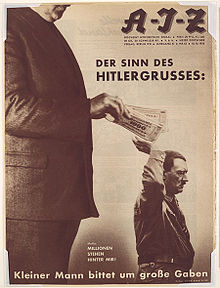

John Heartfield (1891-1968) was a German Dadaist artist. He was a pioneer in the use of art as a political weapon. Some of his photomontages were anti-Nazi and anti-fascist statements. His photomontages satirising Adolf Hitler and the Nazis often subverted Nazi symbols such as the swastika in order to undermine their propaganda message. He is best known for political montages which he had created during the 1930s to expose German Nazism. Some of his famous montages were created during the 1930s and 1940s.

John Heartfield died on April 26, 1968 in East Berlin, German Democratic Republic. From April 15 to July 6, 1993, the second floor of the Museum of Modern Art, MOMA, in New York City was the American venue for an exhibition of Heartfield’s original montages. The show was reviewed in The New York Times.

Max Ernst (1891–1976) was a German painter and graphic artist. Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism. In 1911 Ernst befriended August Macke and joined his Die Rheinischen Expressionisten group of artists, deciding to become an artist, and Paul Gauguin profoundly influenced his approach to art. In 1912 he visited the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne, where works by Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh. His own work was exhibited the same year at Galerie Feldman in Cologne, and then in several group exhibitions in 1913. After Ernst completed his studies in the summer of 1914, his life was interrupted by World War I.

Ernst was demobilized in 1918 and returned to Cologne. In 1919, Ernst visited Paul Klee in Munich and studied paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, which deeply impressed him. The same year, inspired partly by de Chirico and partly by studying mail-order catalogues, teaching-aide manuals, and similar sources, he produced his first collages, a technique which would come to dominate his artistic pursuits in the years to come. Also in 1919 Ernst, social activist Johannes Theodor Baargeld, and several colleagues founded the Cologne Dada group. In 1919–20 Ernst and Baargeld published various short-lived magazines such as Der Strom and die schammade, and organized some Dada exhibitions.

After the Nazi occupation of France, he flee to America, and arrived in the United States in 1941. Along with other artists and friends (Marcel Duchamp and Marc Chagall) who had fled from the war and lived in New York City, Ernst helped inspire the development of American Abstract expressionism.

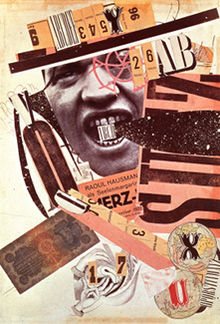

Raoul Hausmann (1886–1971) was an Austrian artist and writer. Hausmann was born in Vienna but moved to Berlin with his parents at the age of 14, in 1901. His earliest art training was from his father, a professional conservator and painter.

After seeing Expressionist paintings in Herwarth Walden’s gallery Der Sturm in 1912, Hausmann started to produce Expressionist prints in Erich Heckel’s studio, and became a staff writer for Walden’s magazine which provided a platform for his earliest polemical writings against the art establishment. In keeping with his Expressionist colleagues, he initially welcomed the war, believing it to be a necessary cleansing of a calcified society.

As one of the key figures in Berlin Dada, his experimental photographic collages and institutional critiques would have a profound influence on the European Avant-Garde in the aftermath of World War I. The photomontage became the technique most associated with Berlin Dada, used extensively by Hausmann, Heartfield, Hoch, and Baader.

Hausmann’s artistic contributions to Dada were purposefully eclectic, consistently blurring the boundaries between visual art, poetry, music, and dance. After his engagement with Dada, Hausmann focused primarily on photography, producing portraits, nudes, and landscapes. He published books and essays on Dada after the war, including Courier Dada, 1958, and Am Anfang War Dada, 1972. Raoul Hausmann died on February 1, 1971, in Limoges.